Some lessons from public health for sustainability and climate campaigners. Our choices are largely not our own — context and norms are far more powerful forces for behavioral change than abstract attitudes. Most people just stick with the default settings. We need to change the default settings.

Tag: climate

Dark Money for to Change the Climate

Data obtained by Greenpeace indicates that there is an almost entirely anonymous funding source funneling far more money than Exxon or the Koch Foundations into the climate denial machine. Also covered in Media Matters and Mother Jones.

A Moral Atmosphere

Bill McKibben rants eloquently about the need for more than individual actions to combat climate change — it’s a systemic problem, the solutions to which can only come with changes to the systems we are all embedded in. Changing your light bulbs and riding a bike are the easy parts. Organizing a devastating political campaign against the fossil fuel interests is much more challenging, and utterly necessary.

E.ON lobbied for stiff sentences against Kingsnorth activists

German energy giant E.ON apparently lobbied cabinet ministers for stiff sentences against Kingsnorth activists, according to papers released under a FOIA style request made by Greenpeace. The company suggested that without “dissuasive” sentences, they might be less willing to invest in generation facilities in the UK in the future. Light sentences for non-violent direct action, and no more coal investment? Sounds like a win-win to me.

Another City is Possible: Cars and Climate

Last week I taught a class at the University of Colorado for a friend. The class is entitled Another City is Possible: Re-Imagining Detroit. She wanted me to talk about the link between cars and climate change. As usual, I didn’t finish putting the talk together until a couple of hours before the class, but it seemed like it worked out pretty well anyway. In fact, I actually got feedback forms from the class just today, and they were almost uniformly awesome to read. As if I might have actually influenced someone’s thinking on how cars and cities interact, and how cities could really be built for people. It makes me want to figure out a way to teach on a regular basis. Here’s an outline of what I said, and some further reading for anyone interested.

What is a car?

For the purposes of this discussion, when I say “car” I mean a machine capable of moving at least 4 people at a speed of greater than 80 km/hr (50 mi/hr). This means cars are big (they take up a lot of space) and cars want to go fast (though in reality they go at about biking speed on average, door-to-door, in urban areas). Cars as we know them today are also heavy, usually in excess of 500 kg (1000 lbs) and numerous, because they’re overwhelmingly privately owned. These four characteristics in combination makes widespread everyday use of automobiles utterly incompatible with cities that are good for people. Big, fast, heavy, numerous machines are intrinsically space and energy intensive, and intrinsically dangerous to small, slow, fragile human beings.

The Takeaways:

- Tailpipe emissions are just the tip of the iceberg — the vast majority of the sustainability problems that cars create have nothing to do with what fuel they use, or how efficiently they use it. Amory Lovins’ carbon-fiber hypercars could run on clean, green unicorn farts, and they’d still be a sustainability disaster.

- The real problems that come from cars are the land use patterns they demand, and the fact that streets and cities built for cars are intrinsically hostile to human beings. In combination, sprawling, low-density land use and unlivable, dangerous streets functionally preclude the use of transit, walking, and biking as mainstream transportation options. In a city built for cars, you have no choice but to drive.

- The good news is that another city is not only possible, it already exists. Very modest density (about 50 people per hectare or 10 dwelling units per acre) is enough to drastically reduce car use, and make low energy transportation commonplace. In combination with good traditional urban design, these cities are extremely livable, healthier, cheaper to maintain, much more sustainable, and much safer than our cities.

- The bad news is Peak Oil is not going to save us. There are a whole lot of unconventional hydrocarbons out there in the oil shale of the Dakotas, the tar sands of Alberta, the ultra-heavy crude of Venezuela’s Orinoco basin, and the ultra-deep water reservoirs off the coast of Brazil, etc. We’d be crazy to burn them all, but hey, maybe we’re crazy. And even if we did run out of oil, it’s entirely possible to electrify our cars for everyday urban use, even with today’s mediocre battery technology. If we want a different kind of city, we’re going to have to choose to build it.

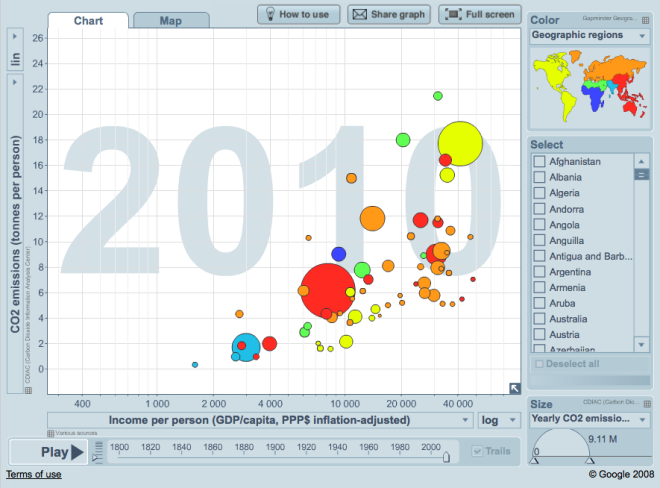

Carbon dioxide data is not on the world’s dashboard

Hans Rosling, world famous Swedish demographer (how many celebrity statisticians are there?) and creator of the Gapminder data visualization tool, offers some thoughts on the importance of timely and transparent reporting of CO2 emissions. If you’re not familiar with his eye-opening presentations already, check out his several TED Talks on YouTube, or explore two centuries worth of CO2 emissions data visually.

Rosling wants all kinds of public data not only to be easily available, but woven into stories that engage the public:

It’s like that basic rule in nutrition: Food that is not eaten has no nutritional value. Data which is not understood has no value.

Continue reading Carbon dioxide data is not on the world’s dashboard

CO2 is not on the world’s dashboard

Hans Rosling, world famous Swedish statistical edutainer, offers some thoughts on the importance of timely and transparent reporting of CO2 emissions. We all know (whether we want to or not) exactly how this thing called GDP is doing, quarter by quarter, but on greenhouse gas emissions, there’s a year long lag.

The Danger in Republican Climate Denial

An Op-Ed in the Houston Chronicle warning fellow conservatives off continued climate denial, lest the GOP be left out of climate change policy decisions altogether as public opinion swings behind the scientific consensus. There’s still plenty of FUD and straw man partisan BS in its language, but the fact of climate change and the farce of painting it as some kind of hoax is called out loud and clear.

As Coasts Rebuild and U.S. Pays, Repeatedly, the Critics Ask Why

The New York Times looks at our national policy of paying to rebuild vulnerable coastal communities, no matter how ill advised their developments might be. In effect, we’ve encouraged people to upscale their beachfront shanties into expensive vacation homes, increasing the value at risk next time a storm hits. As the seas rise, ever more money will be sent down this gopher hole. Instead, we should prohibit future development, map out the most vulnerable locations, and draw up buy-out offers ahead of time, so when disaster strikes, it can be used as an opportunity to re-direct investment into less risky areas.

Climate Change and the Insurance Industry

http://flickr.com/photos/that_chrysler_guy/8139133299/

As the entire eastern seaboard slowly recovers from its lashing by Sandy, insurance companies are bracing for the hurricane’s aftermath and the possibility of another Katrina-scale loss. If there’s any major incumbent business with an incentive to publicly acknowledge the risks and costs of climate change, it’s the insurance industry, and especially the re-insurers — mega-corps that backstop individual insurance companies by pooling their risks globally. These companies can do the math, and what they’ve seen over the last couple of decades is a steady upward trend in both the number of extreme weather events and the resulting insured losses that they’ve been on the hook to cover. The situation is well summarized in a new report from Ceres, entitled Stormy Futures for U.S. Property/Casualty Insurers. They suggest that insurers face an existential risk from climate change.